On Sartre and Beauvoir: From Isolation to Interconnection

For many, including myself, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir are often a first doorway into philosophy. They don’t seem like distant thinkers or heavy textbooks; their writing feels close to life, like a mirror held gently before us.

They discuss choice, freedom, responsibility, and what it means to live authentically. Reading them feels quietly powerful, almost personal, and their words often linger long after the book is closed.

Their ideas remind us we are free, but that freedom is not light and easy. Every choice matters, making us responsible for our lives. Beauvoir adds that freedom is shaped by society, gender, and relationships. Their work urges us to live consciously—not out of habit, but with awareness.

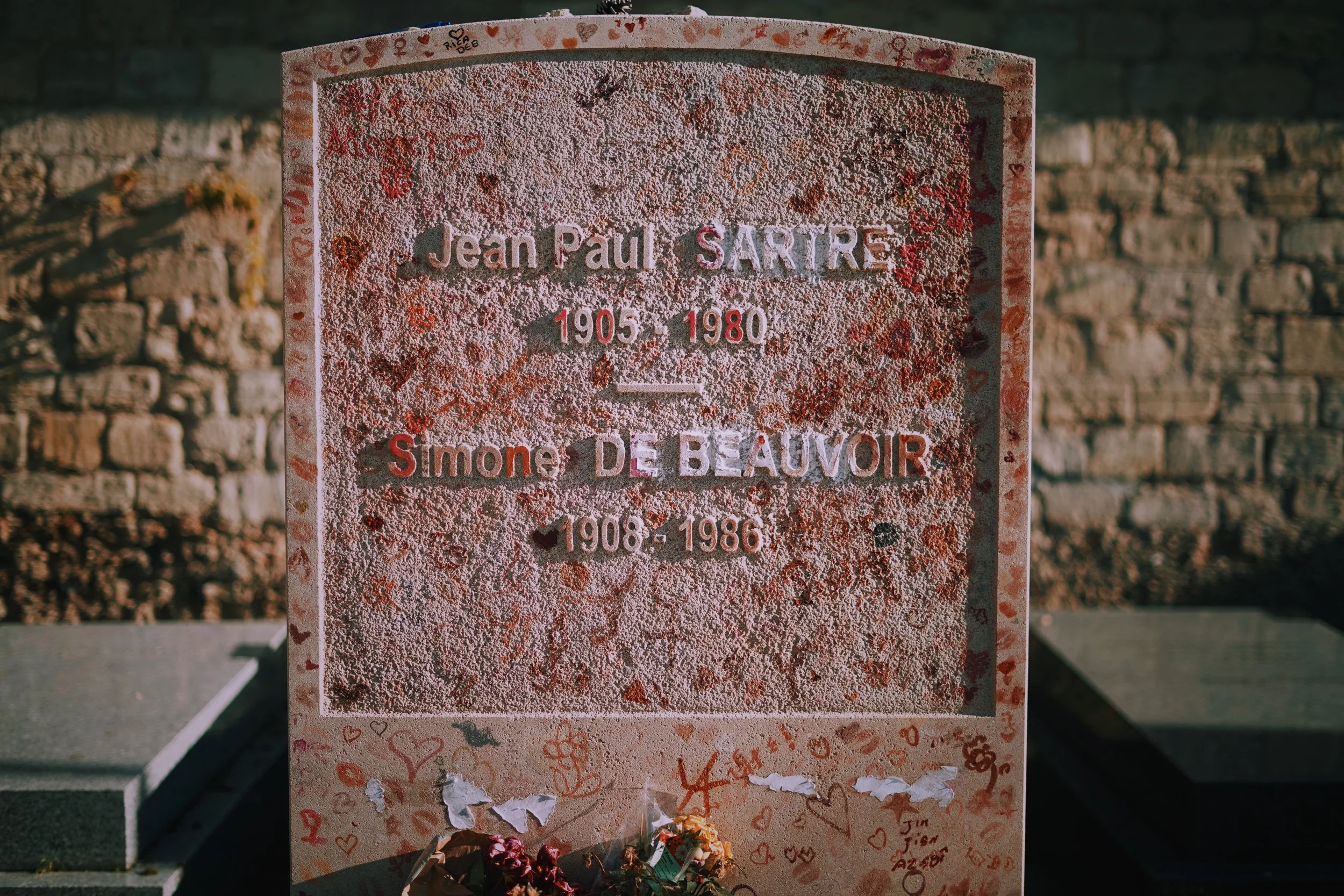

Visiting their shared grave at Montparnasse Cemetery is more than a visit; it feels like paying respect. They lie there together, partners in life and in thought. Their resting place reminds us that freedom means the most when it is shared, not lived alone.

In his 2021 work, Anguish, Abandonment, Despair: Existentialism’s Promise of Hope in a Time of Crisis, William Penne explores the daunting landscape of Jean-Paul Sartre’s early philosophy—a world where human beings are "condemned to be free."

Having spent my college years majoring in philosophy, Penne’s analysis resonates with me deeply.

I remember sitting in my room grappling with the sheer weight of Being and Nothingness, feeling that Sartre had successfully diagnosed the human condition but left us bleeding on the operating table.

I concur with Penne’s central thesis: while Sartre’s framework provides a radical foundation for individual agency, it often leaves the individual drifting in a sea of moral ambiguity, burdened by the weight of the world but lacking a compass for "the good life."

Yet a more robust and optimistic moral direction emerges when we transition from Sartre’s radical individualism to Simone de Beauvoir’s ethics of ambiguity, which grounds personal freedom in the liberation of others.

The Ontological Void

During my studies, the most striking aspect of Sartre’s work was his clinical dissection of existence. It was during these college years that the starkness of his ontological divide truly hit home.

In this magnum opus, Sartre introduces a framework that leaves no room for excuses, distinguishing between two primary modes of being.

Being-in-itself (en-soi), the being of objects. A rock or a table is complete, solid, and coincides exactly with what it is. It has no choice and no potential to be otherwise.

Being-for-itself (pour-soi), the being of human consciousness. Because consciousness is always "of" something else, it is essentially a "nothingness"—a gap in the fullness of being. This "nothingness" is the very source of our freedom; we are not fixed, but are a perpetual "project" of making ourselves.

This freedom, however, leads to a third, more troubling mode: Being-for-others. Sartre famously argued that the "Look" of the Other turns me into an object. When someone watches me, I am no longer a free, transcending subject; I become a "thing" in their world. This leads to his famous conclusion in the play No Exit: "Hell is other people."

In this early Sartrean view, human relations are a constant struggle for dominance—either I objectify you, or you objectify me.

Sartre’s existentialism is defined by a paradox of total liberty and total responsibility. According to Sartre, because there is no pre-determined human nature or divine blueprint, we are entirely responsible for who we become. This realization manifests as anguish—the vertigo one feels when recognizing that they are the sole author of their values.

This freedom is not a gift, but a condemnation. When we choose, we do not simply choose for ourselves; we set a template for what we believe a human being should be. This creates a state of despair, as we must act without the certainty of outcomes, reliant on a future we cannot control and the unpredictable actions of others.

While Sartre insists we are responsible for the society we inhabit, his early work in Being and Nothingness struggles to provide a concrete moral framework, often leaving the individual paralyzed by the sheer scale of their own autonomy.

The limitations of early Sartrean ethics are further highlighted by Sartre’s own historical context. During the period he penned Existentialism is a Humanism, he was navigating an intellectual flirtation with Marxism.

This created a philosophical friction: Marxism emphasizes systemic structures and collective historical forces, whereas Sartre’s early existentialism argued that the individual is free regardless of the systems surrounding them.

This contradiction eventually led Sartre to distance himself from orthodox Marxism in favor of a more anarchistic worldview, but it underscored a missing link in his early theory—the relationship between the self and the "Other."

Freedom as a Shared Project

While Sartre viewed the "Other" as a metaphysical threat, Simone de Beauvoir applied these concepts to the concrete social world in The Second Sex (1949). She observed that while every human consciousness (the "One") naturally tries to define itself against an "Other," society has historically cast women in the permanent role of the Other.

Beauvoir famously stated, "One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman."

She argued that femininity is not a biological destiny but a social construct designed to keep women in a state of immanence (stagnation and objecthood) while men are granted the right to transcendence (the freedom to choose their own path).

By identifying this, Beauvoir moved existentialism away from abstract "nothingness" and toward a critique of real-world oppression.

Where Sartre’s freedom can feel like an isolated burden, Simone de Beauvoir offers a more inclusive and structured path in The Ethics of Ambiguity. For Beauvoir, freedom is not merely the "license" to do as one pleases, but the conscious, spontaneous assumption of projects.

The fundamental difference lies in the conditions of freedom: Sartre’s idividualism emphasized that the individual is free despite their environment, placing the entire moral burden on the solitary actor. Beauvoir’s interdependence argued that the freedom of the self is inextricably linked to the freedom of others. To Beauvoir, one cannot truly be free while participating in or ignoring the oppression of others.

Beauvoir’s ethics are inherently social. She posits that to act without concern for the "Other" is a failure of freedom itself. By establishing that my freedom requires the freedom of those around me, she provides the moral direction that Sartre lacked—a mandate to dismantle systems of oppression as a requirement for personal liberation.

The transition from Being and Nothingness to The Ethics of Ambiguity represents a shift from a "philosophy of the self" to a "philosophy of the world." Sartre’s early work provides the engine—radical freedom, but Beauvoir provides the tracks.

By identifying that the "Self" cannot be truly free if it is surrounded by "Others" who are enslaved or objectified, Beauvoir resolves the Sartrean paradox.

In her view, the anguish of choice is relieved when that choice is directed toward a moral end: the liberation of humanity. This is the "promise of hope" that Penne identifies; existentialism is not a lonely cry in a void, but a call to build a world where every individual can express their transcendence.

Ultimately, while Sartre identifies the raw, terrifying reality of human agency, it is Beauvoir who transforms that terror into a functional ethics. By moving away from the isolated "anguish" of the self and toward a collective "project" of liberation, existentialism ceases to be a philosophy of despair.

Instead, it becomes a promise of hope: a realization that our freedom is fulfilled only when we dismantle the structures—like those described in The Second Sex—that prevent the "Other" from being a peer.

Limit of Choice and a Promise of Hope

While their contributions are foundational, both thinkers have faced significant criticism from later philosophical movements.

Critics of Sartre often point to his "radical freedom" as being blind to material reality. Marxist and structuralist critics argue that Sartre underestimates how much class, economics, and biology limit a person’s choices.

Is a starving person truly "free" to choose their essence in the same way a Parisian intellectual is? His early work is often accused of being overly individualistic, lacking a robust social ethic.

Critics of Beauvoir, particularly from within later waves of feminism, have challenged her reliance on Sartrean categories. Some "difference feminists" argue that by defining "Transcendence" (traditionally associated with men) as the goal, she inadvertently devalues the feminine experiences of care, emotion, and "Immanence."

Furthermore, post-colonial critics like bell hooks have noted that The Second Sex primarily addresses the plight of white, middle-class women, sometimes overlooking how race and class intersect with gender.

Despite these critiques, Penne suggests that the "promise of hope" in existentialism is found in the transition to Beauvoir’s The Ethics of Ambiguity. I agree entirely. Where Sartre’s freedom can feel like a solitary sentence, Beauvoir grounds personal freedom in the liberation of others.

Reciprocal Freedom: My freedom is a hollow shell unless it is reflected back at me by other free beings.. The Collective Project: To truly be free, I must will the freedom of the Other. If I am surrounded by people treated as objects, my own status as a free subject is compromised.

Their philosophy was not just a collection of theories; it was a lived experiment. Sartre and Beauvoir shared one of the most famous intellectual and romantic partnerships in history. They famously rejected the "bourgeois" institution of marriage, opting instead for a pact that allowed for both "necessary" love (their bond with each other) and "contingent" loves (other relationships).

This relationship provided the practical laboratory for their ideas on authenticity and transparency. They served as each other's primary editors and harshest critics, creating a "philosophy of two."

While Sartre often focused on the individual's internal struggle, Beauvoir’s influence pushed him toward political engagement. Their relationship serves as the ultimate example of Beauvoir's ethics: two radical freedoms choosing to intertwine without subsuming one another.

Visiting their shared grave at Montparnasse Cemetery is more than a visit; it feels like paying respect to partners in both life and thought.

Their resting place reminds us that we find our "good life" not by fleeing from the "look" of the Other, but by breaking the chains that keep the Other from looking back at us as an equal. Existentialism, through Beauvoir’s lens, ceases to be a philosophy of isolation and becomes a promise of collective hope.